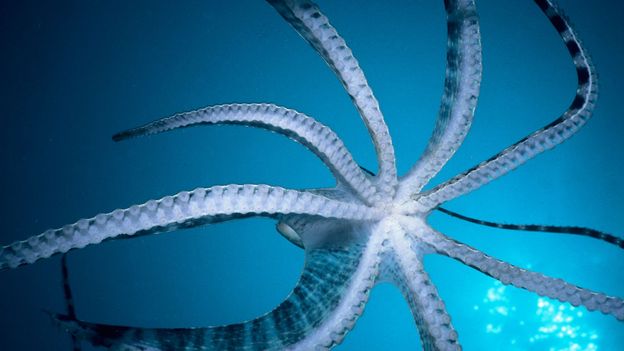

A giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) (Credit: Brandon Cole/naturepl.com)

Bend it like Inky

Play has often been seen as

the preserve of animals with higher cognitive abilities. It is hard to

precisely define it, but in broad terms play is activity that does not

serve an immediately useful function other than enjoyment.

After learning about the work of Lethbridge University colleague Sergio Pellis on mammalian play, Mather wondered whether octopuses play. Working with Seattle Aquarium biologist Roland Anderson, who died in 2014, she devised an experiment.

Roland phoned me and said 'he's bouncing the ball'

They placed eight giant Pacific octopuses

in bare tanks, and over 10 trials gave them floating plastic pill

bottles to investigate. At first the octopuses all put the bottles to

their mouths, apparently to see if they were edible, then discarded

them.

However, after several trials, two of them began blowing

jets of water at the bottles. The bottles were sent tumbling to the

other side of their aquarium, in such a way that the existing current

brought them back to the octopuses. The researchers, who published the study in 1999, argued that this was a form of exploratory play.

"Roland phoned me and said 'he's bouncing the ball'," says Mather.

She

says the octopuses were playing with the bottles. This is similar to

the way human children quickly start to play with unfamiliar objects,

something psychologist Corinne Hutt highlighted several decades ago.

"If

you have an octopus in any new situation, the first thing it does is it

explores," says Mather. "I think it was Hutt who said children will go

from 'what does this object do?' to 'what can I do with this object'.

That's what these octopuses were doing."

Temperamentally tentacled

Mather and Anderson

were happy to conclude that their octopuses were playing, even though

only a couple of them did so. That was because they had previously shown

that octopuses have personalities.

This means that individual

octopuses behave in consistent ways, which differ from their fellows.

This comes as no surprise to people who work with them. For example,

octopuses kept in aquaria are often given names, which relate to how

they respond to people.

Octopuses pass their personality traits onto their offspring

Mather and Anderson set out to measure these personality differences. They kept 44 East Pacific red octopuses

in tanks. Every other day for two weeks, a researcher opened their tank

lids and put their head close to the opening, touched the octopuses

with a test tube brush, and offered them tasty crabs.

The researchers recorded 19 different responses. In a study published in 1993, they identified significant and consistent differences between individuals. For example, some of the octopuses would usually respond passively, while others tended to be inquisitive.

"People

often talk about rainforests as complex environments, but the

near-shore coral reef is much more so," says Mather. "The octopus has

many potential predators and a huge array of potential food, and given

their varied and varying environments it makes a great deal of sense

that individuals do not fit precisely into the same niche."

In a follow-up study published in 2001, they found evidence that octopuses pass their personality traits onto their offspring. Given that they do not raise their young, this suggests their personalities are at least partly genetic.

Mather believes these variations in personality may underpin many of octopuses' advanced cognitive abilities, by allowing them to learn and adapt quickly.

It just shows that there are many other intelligent life forms that we share this planet with!

The blog song for today is: " Octopus´s Garden" by The Beatles. (of course)!!!

TTFN

Master of disguise

The evolutionary arms race

has led animals to develop many devious ways to fool each other. There

are grass snakes that play dead to avoid being eaten, male fish that

pretend to be female to boost their reproductive prospects, and birds

that feign broken wings to lure predators away from vulnerable

offspring.

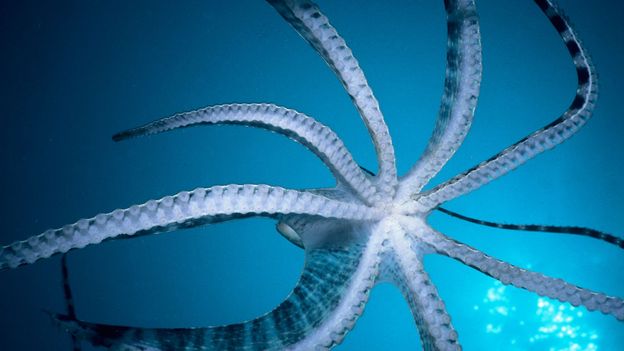

When moving through open water, it mimics a lionfish

Yet of all of nature's charlatans, the mimic octopus must be a leading contender for the title of "master of disguise".

Other

octopuses can change the colour and texture of their skin to give

predators the slip. The mimic is the only octopus that has been observed

impersonating other animals. It can change its shape, movement and

behaviour to impersonate at least 15 different species.

When travelling across sand, it can flatten its arms against its body and undulate like a venomous banded sole. When moving through open water, it mimics a lionfish, which is also venomous. Another trick is to put six of its arms into a hole and use the remaining two to look like a banded sea krait, a type of sea snake that is, of course, venomous.

A problem solved

Octopuses can use trial and error to find the best way to get what they want.

They have different strategies to achieve the same ends

In work published in 2007, Mather and Anderson observed giant Pacific octopuses trying to get at the meat in different types of shellfish.

They simply broke open fragile mussels, pulled apart stronger Manila

clams, and used their tongue-like radulas to drill into very strong

littleneck clams.

When given a choice of the three, the octopuses

favoured the mussels, presumably because they required less effort to

get a meal.

The researchers then tried to confuse their subjects

by wiring Manila clams shut. However, the octopuses simply switched

technique. Mather concluded that they could learn based on non-visual

information.

"It told us that octopuses are problem-solvers," she

says. "They have different strategies to achieve the same ends, and they

will use whichever is easiest first."

Mazes for molluscs

During fieldwork in

Bermuda, Mather observed octopuses returning to their dens after hunting

trips without retracing their outgoing routes. They also visited

different parts of their ranges one after another on subsequent hunts

and days.

Most of the octopuses had learned to recognise which maze they were in.

In a study published in 1991, she concluded that octopuses have complex memory abilities. They can remember the values of known food locations, and information about places they have recently visited.

When

animals use landmarks to help them navigate, they have to be understand

the landmarks' relevance within their contexts. This ability, known as

conditional discrimination, has traditionally been seen as a form of

complex learning: something only backboned "vertebrates" can do.

In work published in 2007, Jean Boal of Millersville University in Pennsylvania placed California two-spot octopuses

in two different mazes. In each case they had to travel from the middle

of a brightly-lit tank to reach a dark den, an environment they

preferred. To get there they had to avoid a false burrow, which was

blocked by an upside-down glass jar.

After five trial runs, most

of the octopuses had learned to recognise which maze they were in and

immediately headed for the correct burrow. This, Boal concluded, meant octopuses do have conditional discrimination abilities.

A mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus) (Credit: Jeff Rotman/naturepl.com)

Similarly different

In many ways, octopuses' brains are rather like ours.

They

have folded lobes, similar to those of vertebrate brains, which are

thought to be a sign of complexity. What's more, the electrical patterns

they generate are similar to those of mammals.

The last common ancestor of humans and octopuses lived a long time ago

Octopuses also have monocular vision,

meaning they favour the vision from one eye over that from the other.

This trait tends to arise in species where the two halves of the brain

have different specialisations. It was originally considered uniquely

human, and is associated with higher cognitive skills such as language.

Octopuses even store memories in a similar way to humans. They use a process called long-term potentiation, which strengthens the links between brain cells.

These

similarities are startling. The last common ancestor of humans and

octopuses lived a long time ago, probably quite early in the history of

multicellular life, and was a simple animal. That means the similarities

in brain structure have evolved independently.

Even more fascinating than the similarities, however, are the differences.

Octopus intelligence may be distributed over a network of neurons, a little bit like the internet

More

than half of an octopus's 500 million nervous system cells are in their

arms. That means the eight limbs can either act on their own or in

coordination with each other.

Researchers who cut off an octopus's arm found that it recoiled when they pinched it, even after an hour detached from the rest of the octopus. Clearly, the arms can act independently to some extent.

While

the human brain can be seen as a central controller, octopus

intelligence may be distributed over a network of neurons, a little bit

like the internet.

If this is true, the insights octopuses offer

extend way beyond their advanced cognitive and escapology abilities.

Inky and his relatives may force us to think in a new way about the

nature of intelligence.